This has to have been one of the more trying seasons my soul has endured. As I try to remain optimistic and joyful about the possibilities of being a teacher, I must combat the continual disillusionment one feels when faced with the grim prospects of our current economic malaise, and its effect on young, passionate educators such as myself. My wife Dolly has had to cope with an agonizingly drawn-out medical issue since September, as all the while I remain unemployed, despite my best efforts to secure myself a position in the maddening bureaucracy that is education. The problem, of course, is that there are no jobs to be had. The jobs that are available are reserved for twenty- to thirty-year veterans cycling through the tenure system, and while I bear them no ill will for desperately holding on to what is rightfully theirs, it prevents me and legions of my contemporaries from being given a chance to do what we have been trained for, even as burnt-out fifty-somethings lazily spout curriculum to generations of students that are clearly missing the enthusiasm and relevance younger educators bring to the classroom. I have to take solace wherever I can get it, and so in addition to the powerful, unconditional love and support of my wife, family and friends, I am always returning to…MUSIC. I think that, in times like these, music is perhaps even more essential that it would usually be. It is like therapy given by and to the ages; it is as though all the lessons and struggles that have ever been in human history can be echoed and eased by the healing magic of music. With that in mind, these items below have some POTENT magic in them, folks…

Nov 23, 2011

Doris Duke: "I'm A Loser"

Yeah, I know, starting out on a bummer note. But c’mon, what is misery if not a universal characteristic? This record isn’t “northern soul,” or “southern soul,” or even “deep soul”...it’s heartbroken soul. I don’t think I have heard such pain on a record in a very, very long time, if ever. Sure, many artists indulge in a track here and there that revels in melancholy, but rarely are they so bold as to create a whole album around that feeling. The sad thing is, when you hear forty to fifty minutes of such low, down-and-out tragedy, you can’t help but worry about the person behind it all. Doris Duke, of course, is a distant memory to most, and so who knows what inspired her to wreak such emotional havoc on wax. She absolutely succeeds in creating a mood; a bleak, scorched-earth soundscape aided immensely by Jerry “Swamp Dogg” Williams’ able production and songwriting skills. Songs like “I Can’t Do Without You” and “Ghost Of Myself” are world-weary, heart-wrenching pleas made palatable by the church-ified, Southern-rooted grooving of the session band, featuring Jesse Carr and (possibly) Duane Allman on guitars. Other tunes, like “He’s Gone” and “Feet Start Walking,” have a vacant, spacious energy to them that suits the material perfectly, mirroring the empty resignation apparent in Duke’s voice; she sings like a person who has nothing left to give, nothing emotional left to invest. The truth is, this is one of those underground masterpieces that will never be heard by enough people, yet that is what makes it so desirable to the committed few, and indeed, records like these are the very reason the term “deep soul” was coined in the first place. Keep on diggin, y’all.

Roy Ayers Ubiquity: "Change Up The Groove"

This one always seems to get lost in the heralded, cherished footsteps of Ayers’ early ‘70’s output. It’s not as raw as “Ubiquity,” not as rare as “He’s Coming,” not as iconic as “Red, Black & Green.” It is, however, exceptional in its own right and on its own terms, and so if you can for one moment forget whatever preference you may have for the aforementioned records and open up your mind to this one, you will be pleasantly surprised. The title cut serves as a sort of signifier for the theme of the album, featuring Ayers’ trademark, knotty vibes riffs against a pounding, bass-heavy, jazz-funk backdrop. Songs like “Sensitize” and “Fikisha (To Help Someone To Arrive)” operate in that unique space that only Ayers has ever managed to navigate successfully, that is, on the borderline between avant-garde spiritual jazz and accessible ‘70’s funk. Even the cover choices here stand out, though one may feel some trepidation when they see “Theme From M.A.S.H.” and “Feel Like Makin’ Love” on the track listing. What might have been ill-conceived filler material in the hands of lesser artists is rendered with mastery by Ayers and his Ubiquity crew, transcending the MOR origins of the songs themselves to fit into the band’s greater spiritual-jazz-funk vision. The album closes with the break-beat staple “The Boogie Back,” street-funk drumming and fuzz guitars breaking bread with one another until the inevitable fade-out occurs. While “Change Up The Groove” may not be elevated into the pantheon of Roy Ayers’ most classic LP’s, after even a cursory listen, it is confusing as to why that is the case. ‘Cause it’s the shit.

Norman Feels: "Norman Feels"

The minute this one kicks off, you know you’re listening to the rare groove goods, though, like me, you probably have no idea who in the hell this Norman Feels guy is. Recorded in Detroit with a handful of Motown’s Funk Brothers and arrangements by the legendary David Van De Pitte, this music was clearly inspired by “What’s Going On”-era Marvin Gaye. The formula somehow works, though, for even as Feels rocks a high falsetto throughout the album, he doesn’t really sound like Marvin at all. Much like similar records by Mike James Kirkland and Leroy Hutson, Norman Feels is striving for a “conscious-political-orchestral-romantic-funk-soul-classic-‘70’s” vibe, and yet also like Kirkland and Hutson, he falls just short of the mark, which is where the charm of a piece like this lies anyhow. In some ways, music like this speaks more of the lasting, super-charged impact of Marvin Gaye’s influence than it does of its own merit. Still, I dig Feels’ energy here, and the grimy, down-low clavinet build-up on album opener “Don’t” is worth the price of admission alone. The common thread between “What’s Going On” and this record are the arrangements by Van De Pitte, who adds his subtle, tasteful touch to everything here. Anyone who’s listened to enough ‘70’s soul knows that “subtle” and “tasteful” are not often the adjectives you’d use to describe the ham-handed meanderings of less talented orchestrators, a fact that only makes Van De Pitte’s textures that much more appealing. Meanwhile, Norman Feels attempts bold re-constructions of Detroit standards like “My World Is Empty Without You,” set alongside his own singular, original numbers like the dark, moody “Something In Me,” the bouncy, almost-Philly groove of “Yes You Did,” and the psychedelic, topical “Today.” Sure, it’s impossible to imagine an album like this existing without Marvin Gaye. That truth, however, becomes irrelevant after repeated listens, and when you reach the end of the record, which closes with the gorgeous, grandiose “Everything Is Going Our Way,” you can’t help but be impressed, and even astounded, by the beauty of it all.

Hearts Of Stone: "Stop The World, We Wanna Get On"

Continuing along with the Motown auxiliary theme, here’s an LP that fell through the cracks almost immediately upon its release in 1970. Distributed on the tiny VIP subsidiary label, the back cover proudly proclaims “The Motown Sound,” but alas, it was not meant to be for the Hearts Of Stone, a group obviously and heavily stylized in the Temptations/Four Tops tradition. Given a larger exposure and a greater amount of promotion, this album could have done better, though there is nothing here to rival the work of Motown’s more famous acts. There are, however, some key tracks for the psych-funk heads, such as the fuzz-guitar-infused “You Gotta Sacrifice (We Gotta Sacrifice)” and the cover of Sly’s “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).” The Sly influence, in fact, pervades the material, as the group adds acapella, gospel-esque break-downs and handclaps to many of the songs, as well as generous slatherings of organ and rock guitar. Some may contend that this LP serves mainly as an item for Motown completists, but I would broaden that assumption to include those interested in the incalculable impact Sly Stone had on music at this particular juncture in history. It’s not a perfect record by any stretch, but its best moments are wonderful. These guys just wanted to take the listener higher, even if they had to turn to the West Coast to get their inspiration.

Sidney Joe Qualls: "I Enjoy Loving You"

This is the best Chicago soul record Al Green never made. Confused? I was too. Qualls’ vocals sound so much like Green on some of these tracks, you’d swear Al was in the studio recording these under an AKA. But no, Sidney Joe is a real person, one who owes an enormous debt to the oft-praised (and praising) soul legend. Still, Qualls does manage to do his own thing, as on the title track, which certainly sounds more Chicago-bluesy than it does Hi Records-polished. It’s in his vocal inflections where the resemblance becomes almost too much to believe, a fact not lost on other reviewers of this album. I suspect the similarity comes from both men’s origins in the Baptist church, and some accounts even have it that the two were born in the same town, in Arkansas. Whatever the case, this is a great soul record, comparisons aside. “Shut Your Mouth” is as tough as its name indicates, a condemnation of double-speak and hypocrisy that seemed to be a common thread in early ‘70’s soul. “Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love” nearly—nearly—beats Green and Mitchell at their own game, and it’s funny to hear what are likely Chicago session musicians sounding all Memphis-like. “Run To Me” has more of an uptown sound a la Curtis Mayfield, at least in the music, though Qualls still yowls and pleads like you-know-who over the top of it. The cover of Gamble and Huff’s “If You Don’t Know Me By Now,” made famous by Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes, adds an entirely different perspective to the well-known tune, even switching the modulation in the chorus a bit. “Please Help Me” comes off like a more minimally-arranged Impressions track, with the strings extremely low in the mix, as a cascading, glowing electric piano leads the groove. Qualls is a talented, gifted singer, and his selection of material here is exemplary. Though it is unquestionably difficult to get past the Al Green-isms in his voice, one will find that it does not really matter in the grand scheme of things, and in fact reinforces the intriguing nature of this whole project. Veering wildly between Hi Studio imitations and lovely, delicate Windy City intricacies, it is inconceivable to not be fascinated by the weirdness of Sidney Joe Qualls, quite possibly the world’s only “other Al Green.”

Rance Allen Group: "Say My Friend"

So, in keeping with my recent obsession of looking for rare gospel-funk LP’s, here’s one of the “holy grails” (pun intended) of the genre. I must admit that I did not seek this out so much for its gospel as I did for its association with the Mizell Brothers, the storied production team behind such ‘70’s jazz-funk masterpieces as Donald Byrd’s “Places and Spaces” and Bobbi Humphrey’s “Blacks And Blues.” Rance Allen, however, has an interesting history in and of himself, from his roots as a traveling gospel singer to his early ‘70’s breakthrough on the Truth subsidiary of the Stax label. The music on this record features the trademark “Mizell Sound,” with lilting arrangements and ethereal background vocals floating just above the driving funk. When combined with Rance’s vocal acrobatics and the Allen brothers’ impeccable musicianship, a unique item in the Mizell canon is created. The best tunes play on the strengths of the multiple parties involved, with “Reason To Survive” and “Peace Of Mind” being the obvious standouts. The former rides a mid-tempo rhythm guitar at its center, while the latter is full of the airy fusion vibe present on so many of the Mizells’ most lauded work. While I wasn’t exactly sure what to expect in getting into this album—gospel is not my specialty, after all—I was quite impressed, and not just because of the Mizell factor, but because the Rance Allen Group stood on its own as a musical force to be reckoned with.

Sound Experience: "Don't Fight The Feeling"

Now. You may be thinking, “Dylan, you’re getting away from the kinda shit that we KNOW you like the most…the hard, biting, rampaging FONK. All this sweet soul and gospel stuff is cool, sure, but, c’mon…where’s the grease?” Fear not, friends, for I have a record to assuage your doubts. Sound Experience was a large, horn-driven Philly group that, according to most accounts, were more known for their fiery live performances than they were for their studio abilities. While I can certainly see how the stomping grooves here would have translated well in a live setting, the band does just fine without an audience, studio polish and all. Their sound is something of a mix between early Kool & The Gang and pre-saccharine Philly outfits like Yellow Sunshine, and though they do try their hand at a few half-baked ballads, their strength is clearly in the heavy funk. “Your Love Belongs To Me” is not a statement so much as it is a command, as the musicians roil, percolate and syncopate underneath the vocals. “Step People” is, indeed, a stepper, strolling and swinging along, eventually fading into the monstrous title track, which delivers a loud, anarchic dose of funk-rock, one that has guitars, clavinet, horns and party whistles in full effect. “Going Through The Motions” has a bit of a Latin soul feel to it, which blends with a Motown-sounding melody to make for quite an interesting track. “You’ve Broken My Heart” has more of that same Latin-disco energy, starting with a thudding clavinet and then moving into broken-time, horn-powered weirdness, albeit with lovely group soul vocals up top. The final track, “Devil With A Bust,” is perhaps the most well-known number, as it has provided sample fodder for many a break-starved DJ. Forget the break, though, and listen to the tune, ‘cause it jams as hard as any funk from its era. Synths, phased guitars and reverb-laden vocals move it along, stirring up a slinky, slithering, sinister sort of momentum, until said break allows for some breathing space. Finally, the band comes back in, eerie harmonica and grinding funk maelstrom dissolving into a bass solo and then nothingness. “Sound Experience” could not have been more appropriately named, as the listener will not be quite the same after this album.

Walter Bishop, Jr.: "Coral Keys"

This is one of the prettiest LP’s I’ve heard, but not pretty in the flowery, sickly-sweet sense. This is pretty in the same way that a foggy morning is pretty, or a desert is pretty—pretty but complicated. Bishop plays these organic, flowing lines on the piano that feel as though they descend in and out of each other infinitely, while other notables like Idris Muhammad and Harold Vick add their own rhythm and flavor. The tag “spiritual jazz” is often thrown around in describing music of this kind, but unlike other meaningless labels, it does make sense in such a context. The players definitely appear to be looking for some intangible break-through to a higher power in their searching, exploratory solos, though exactly what higher power they are attempting to communicate with is unclear. In the early ‘70’s, jazz and funk artists were incorporating a great deal of pan-theistic elements into their creativity, and so the lines often seemed blurred between such wildly differing forces as ancient African gods, Christian trinities, Hindu and/or Buddhist meditations. This approach is startling, in that it appeals to more personal, individualistic feelings of spirituality rather than specific, denominational worship. This heartfelt spirituality, along with an emphasis on unity, melodic mantras and progressive thinking, is evident throughout the “Coral Keys” album, so much so that it achieves its goal of transcending religion, musical styles and preconceived notions. Not often does one stumble across something this beautiful.

The Montclairs: "Dreaming Out Of Season"

Sweet, sweet soul on the small, Louisiana-based Paula label. The Montclairs, from East St. Louis, share a number of the collective aspects prevalent on much of the group soul being released around the country at the time this record came out (1972). Fragile, accentuating strings pepper the arrangements, as the Montclairs step out with smooth harmonies and a typical lead falsetto sound. Then there are the moments on the LP that make you realize this was a local, small-label project at its core, and so the singers, along with noted producer/musician Oliver Sain, have the opportunity to do more experimentation than would usually be prudent on such an undertaking. The title track is perfect, a masterpiece in league with work by better-known artists like the Delfonics, Stylistics, Dells, Dramatics, etc. The other essential track is the epic, eight-minute “Do I Stand A Chance,” which starts out more or less in pedestrian fashion, with a lightly funky rhythm dancing around a pleading falsetto. As the track proceeds, however, the vocals start to become more disembodied, almost ghostly, bathed in reverb and adding an unsettling ghostliness to what would otherwise be a fairly standard genre exercise. It can only be described as “acid music for sweet soul heads.” The rest of the album has its surprises also, from the singer-songwriter-ish, acoustic guitar-led bridge of “Beggin’ Is Hard To Do,” to the pensive, quasi-folk-soul of “Just Can’t Get Away.” While this record did respectably well in the local-label market, due to the regional success of its title cut, it is almost positive that very few now remember the Montclairs, and what a shame, ‘cause these dudes bring the heat on the sweet soul tip. Check ‘em out.

David Ruffin: "David Ruffin" (Motown label 1973)

There are few stories in rock and R&B as tragic as David Ruffin’s. Pegged as an impossible-to-work-with troublemaker in the Motown organization early on, unceremoniously fired from the Temptations at the height of his popularity within the group, a solo career of mixed results and success, a near-lifetime of on-again/off-again addiction, and then, in his final chapter, the victim of an overdose (thought by some to be an unsolved murder/robbery) at the age of fifty. Given this history, it is an emotional experience to listen to Ruffin sing, riddled as his voice is with fervor, sadness and heartbreak. This particular album of his focuses in on an everyman, working-class theme, quite literally with titles like “The Common Man,” “I’m Just A Mortal Man,” and “A Day In The Life Of A Working Man.” It’s like Ruffin is going out of his way, over and over again, to explain that he is a flawed human being, turning what was already a bittersweet feeling for the listener into outright depression, and devastation. Still, it’s a beautiful record in its own shattered way, with some of Ruffin’s all-time highlights, like his covers of “I Miss You” and “If Loving You Is Wrong (I Don’t Want To Be Right),” as well as the cynical, hard-edged funk of “Blood Donors Needed (Give All You Can).” On this album, David Ruffin is a man broken but not yet destroyed, and though there would be a long, slow decline in the years to come, his talent and spirit shine brightly here.

Oct 9, 2011

Catalyst: "A Tear And A Smile"

Catalyst is one of those groups I thought I’d never find on original vinyl. They only made four albums for the Cobblestone and Muse labels, all of which are incredibly obscure, even by rare groove standards. Their fourth and last, “A Tear And A Smile,” may be the rarest of the bunch, and is by a long shot the funkiest. While their earlier records featured sporadic soul-jazz jamming in the midst of heady, almost avant-garde spiritual cuts, “Tear…” is no-holds-barred funk-fusion. The opening track, “The Demon,” is broken into two parts, starting with a grim, dirge-like synth-funk groove, moving through a hard fusion section, finally bursting into all-out street-funk towards the end. Other highlights include “Fifty Second Street Boogie Down,” which is as earthy and strutting as its title suggests, and the haunting “Suite For Albeniz,” a series of variations on a Spanish-flamenco theme that beats groups like Weather Report at the whole “world-fusion” game. In the ‘70’s, fusion groups were a dime a dozen, but very few ever sounded this intense, or committed to their craft. It is truly a shame that, after “A Tear And A Smile” failed to make a major (or even minor) commercial impact, the Philadelphia-based band called it quits.

Prince Phillip Mitchell: "Make It Good"

This album cover is hilarious. Mitchell seems a bit confused as to what image it is that he wants to convey; on the front he strikes an extremely generic, late ‘70’s, “I’m chillin’ with this chick” pose, and then on the back, he is curiously wearing a pair of Bootsy glasses. …? Perhaps no-one bothered to tell him that there was already a major star in the R&B world cultivating that exact same persona, and making a LOT more money doing it. However, don’t let the rather schizophrenic album photos fool you…this is quite an amazing record. Mitchell scored big as a songwriter for a laundry list of soul acts throughout the ‘70’s, and so when he struck out on his own, he’d had years to perfect his unique style, which is in all its full glory here. “Star Of The Ghetto” kicks things off, with Prince Phillip demonstrating an impressive falsetto yowl over dreamy keys, until his mom yells at him to “get out the house with that noise!” He then proceeds to narrate the history of his life in music, despite both of his parents’ objections, over an unbelievable, conga-driven, dance-funk groove. He concludes that he doesn’t care whether or not he makes the big-time, as long as he’s a “star in the ghetto” he’ll be satisfied. This is interesting lyrical material, to say the least, and not exactly your typical late ‘70’s R&B fare. The rest of the album features a mix of Southern soul flavor mixed with uptown arrangements and changes, best displayed on slow jams like “Falling From Heaven” and “Only Smoke Remains.” The cut for the funk heads, though, is the strangely-titled “You’ll Throw Bricks At Him.” It starts out with an oft-sampled harp-over-breakbeat intro, then goes into an insane, pocket-heavy funk throw-down, somewhere in between the Meters, Dorothy Ashby, Lamont Dozier and the Isley Brothers. If that combination isn’t enough to pique your curiosity, I don’t know what to tell you. Regardless, this is a great, underrated album, and after a few listens, you’ll begin to think, “ya know, I think this guy deserves to be wearin’ those Bootsy glasses, ‘cause dis shit is off the chain!”

Shuggie Otis: "Inspiration Information"

So, I just had to mention this one as being in the company of my recent finds, as anyone who is even a casual fan of ‘70’s funk knows what a holy grail this is, particularly in its OG vinyl incarnation. I’m not sure it’s necessary to bore you with yet another tirade about how “brilliant,” “futuristic” and “ahead-of-its-time” this album seems, though it is all of those things. The truth is that it’s all been said before, mostly in the wake of Luaka Bop’s re-release of this classic LP some years back. What I did think, however, is that my (very) recent review of Van Hunt’s new album might serve as an interesting comparison. Both Shuggie and Van are restless souls, and Van Hunt’s newest is the “Inspiration Information” of his own career. While people often discuss how revelatory Shuggie’s experimentation on “Inspiration…” is, what is often overlooked is that it might not have been fun to actually BE the Shuggie Otis that made such a record, as he most certainly knew that it was not something his peers would quite comprehend, and that, if it were ever to receive the accolades and appreciation it deserved, it would be years after his own star had faded. Still, thank goodness he did make “Inspiration…,” ‘cause it continues to be a standard-bearer for the kind of creative innovation that only a select few can actually attain. From the lucid summer dreaming of the title track, to the personality crisis of “Aht Uh Mi Hed,” to the moody, all-instrumental B-side of the album, this really is one of those pieces of art that people are still racing to catch up to. In keeping with my aforementioned comparison, I can’t help but think that Van Hunt’s latest occupies the same sort of space. Van Hunt and Shuggie Otis…idiosyncratic to a fault, but what would the world of music be without them?

Alice Clark: "Alice Clark"

I paid $15 for this, at a tiny store near Tacoma, WA. The circumstances by which I obtained it were a bit bizarre…there was only a tiny selection of records on display that were actually priced, while on shelves below, there sat hundreds, maybe thousands, of much more interesting, valuable, and un-priced records. I would have liked to have taken several of these with me, but being on a limited budget, and not knowing what any of them would cost me, I settled on this single platter. I took it to the girl behind the counter, and she says, “oh, the records underneath aren’t for sale yet.” Are you kidding me?!? I insisted I had to leave the store with the LP I had selected, and eventually she quoted me a price, though not without some more unnecessary side-stepping. $15 may not seem like a bargain, but those in the know will recognize that, for this particular record, it’s an absolute steal. Oh yeah, and did I mention that it was a white-label DJ copy, in mint condition?

The music recorded here is sublime, akin to an early fall day where, while you may be lamenting the loss of the summer, you are nevertheless anxious for the cold winds and dark nights to take hold. Alice Clark’s voice is perfection, very much in the ‘70’s soul diva tradition, but with none of the histrionics so often associated with that genre. She has remarkable range and control, never seeming to over-exert to achieve the vocal impact desired. When paired with Bob Shad’s crystal-clear, warm production and Ernie Wilkins’ complex, subtle arrangements, the end result is transcendent, heavenly, ethereal, miraculous. Individual track analysis is fairly irrelevant here; this is the kind of album that has to be listened to as a whole to be fully appreciated. I must say, I am so happy to have found this, even if it did require a small amount of diplomatic haggling on my part. This is an LP for all moods and surroundings; it feels equally comfortable in the drunkenness of the wee hours as it does with coffee on the following hung-over morning.

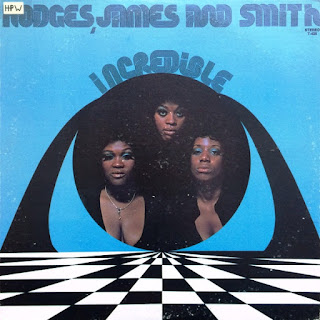

Hodges, James And Smith: "Incredible"

The first thing that caught my eye about this one was the funky West Coast rhythm section listed in the credits—Paul Humphrey on drums, Joe Sample on keys, Wilton Felder on bass, Roland Bautista on guitar. In the ‘70’s, this was a session engineer’s dream team, the kind of cats that could make anybody’s music sound good. It helps, however, that Hodges, James And Smith are no slouches in the vocal department. These ladies can swang, sang and testify with the best of ‘em, and on this LP they are given a beautiful set of grooves over which to demonstrate their considerable talent. The listener is reeled in immediately with the opening “Turn The People On,” where Roland Bautista makes his presence known with the kind of screaming guitar leads he would later bring to such diverse artists as Earth, Wind & Fire, George Duke, and Morris Day. From there the girls stretch out into all kinds of different bags, from the juke-joint stomp of “Rock Me Baby/Steamroller,” to the near-gospel of “Oh,” to delicate, heartbroken slow jams like “Signal Your Intention” and “You Take My Love For Granted.” They even try their hand at laid-back Latin rhythms on the LP’s final cut, “Love Was Just A Word.” Needless to say, the experimentation with multiple styles pays off, and wraps itself up into a remarkable whole, one in which these gifted women strut their stuff and sing their asses off. This is the kind of obscure record that justifies all the endless hours of crate-digging—or, as my friend Barry put it, the “vinyl archaeology”—that so many of us are consumed by.

The Futures: "Past, Present, And The Futures"

Success never really happened for Philly-based group the Futures, though it deserved to. That lack of success, and thus distribution, is a major contributing factor as to why their records are so difficult to find nowadays. What I dig about the Futures is that they are somewhat atypical of the Philly sound that so many of their contemporaries embraced. Why this is the case is a bit of a mystery, as the musicians and arrangers responsible for their sound are the same people that worked magic on the Futures’ more popular peers…behind-the-scenes masterminds like Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff, Roland Chambers, Bobby Eli, etc. I think what stands out immediately for the listener is that the arrangements here are more minimal than the average Philly International session. While songs like “Party Time Man” and “Sunshine And You” might fit neatly into the famed label’s output of string-laden disco hits, tracks like “Ain’t Got Time Fa Nothing” and “Come To Me (When Your Love Is Down)” have a timeless, unhurried feel to them that foregoes the heavily orchestrated backings for a striking emphasis on the vocal group’s sterling harmonies. “Ain’t Got Time…,” in fact, has a rare-groove vibe that still sounds light years beyond the era in which it was recorded, the sort of thing that current sampling beat-heads love. Throughout the LP, the Futures’ vocals are highlighted in such a way as to make them the main focus for the listener, a sonic pleasure that seems to become more rewarding with each repeated spin. The name of the group itself appears to be rather prescient, as with the hindsight of modern musical perspective, we are able to see that these cats had a vision that exceeded the expectations of their own time and space.

The Blackbyrds: "Cornbread, Earl And Me"

Been searching for this one for a while now! The Blackbyrds have always been one of my favorite groups, I think because they keep the excesses of ‘70’s jazz-funk to a minimum and focus primarily on the groove. “Cornbread, Earl And Me” is the most difficult album of theirs to find, probably because it doesn’t contain any of the group’s big hits, and instead presents a moody soundtrack vision of the film it accompanies. Donald Byrd composed the score, and is even spotlighted on solo trumpet on a couple of tunes. The combination of Byrd’s lyrical, elegiac writing and the Blackbyrds’ significant musical chops is wonderful, an “arrangements-as-played-by” equation that works surprisingly well. The music here is definitely recognizable as theme-oriented, film-driven composition, particularly in the more heavily orchestrated segments. Funk fans, though, will still find much to like, as the Blackbyrds grind through hard-hitting jams like “Cornbread,” “The One-Eye Two-Step,” “Soulful Source,” and the much-sampled “Wilford’s Gone.” While these guys certainly garnered their fair share of commercial success, it still feels like they’re an underrated band, as they are able to tear through technically-proficient funkiness like few others of their generation.

Bobby Womack: "Understanding"

Woooooooooooo!!!!!! This is some down-and-dirty, FONKY soul right here; it didn’t leave the turntable for about a month after the first time I played it! This is an extremely rare occasion for me, considering the amount of records I cycle through during any given four-week period. Not exactly a rare LP, but that’s neither here nor there when you’re in the company of a masterpiece. You may think I’m exaggerating a bit, but this matches up with any funk/soul classic you’d care to mention from the same time-frame. It encompasses the gutsiness of Riot-era Sly, the guitar theatrics of early Funkadelic, the uptown smoothness of the Philly and Chicago vocal groups, the politics of Marvin and Stevie, and even the Southern, gospel-drenched, country-soul flavor of ‘70’s Stax. Womack’s razor-shredding voice testifies like a man possessed, hearkening back to the days when “soul music” wasn’t even a term, and the only place to hear such raw passion was the church. However, this is no gospel album, as Womack mines deeply personal, secular territory to carve out a feeling for the material. The blistering “I Can Understand It” was a huge hit for the New Birth, but Bobby’s original rendition is just as interesting. It’s slower, and has more of a deliberate, loping drag to it, eventually propelling itself into an all-out funk-rock stomp via Womack’s fiery guitar leads. “Woman’s Gotta Have It” follows, an effortless, mid-tempo number that is about precisely what you think it is. Other key tracks are the near-country “Got To Get You Back,” the ferocious, thudding “Simple Man,” the back-porch, blues-with-strings meditation “Ruby Dean,” and the topical early ‘70’s cut “Harry Hippie,” a tune actually written by Jim Ford, yet found in its most definitive incarnation here. Bobby Womack pulled off something unique with this LP, in that he took all the complex components that made early ‘70’s soul so fascinating, then added a gutbucket earthiness to the brew that kept the head nodding even as the mind contemplated. A gem.

Sep 29, 2011

Van Hunt: "What Were You Hoping For?"

I was telling a friend earlier today that, when I first heard Van Hunt’s “Dust,” off his self-titled debut album, it signaled a sea change in music for me. Here was someone who was using all the elements hitherto explored in the worlds of R&B, rock, and pop, and yet there was an immediate, audible difference in Van Hunt’s material. Unlike other artists examining the music of the past, he wasn’t doing so in an isolated, deliberately retro sense. He was contemporary and vibrantly so, with all the psychedelic flair of the Beatles and Hendrix, but in a strictly post-millennial framework. Everybody instantly wanted to draw comparisons to Prince, but that wasn’t quite correct either. While both artists were certainly genre-defying, Hunt had an edgier, bleaker outlook that was as honest as it was uncompromising. Tracks like the aforementioned “Dust” and “Out Of The Sky” were among the funkiest things released in their DECADE; this cat was poised for something big.

A couple of years later came the On The Jungle Floor record, which should have made Van Hunt a superstar. Radio-ready singles like “If I Take You Home” and “Hot Stage Lights” came bursting out of the gates, while tender ballads like “Daredevil, Baby” and “Mean Sleep” showed that Hunt could pen a beautiful melodic line with the best of them. Still, I have to confess to the fact that, while I liked this album, after the initial excitement wore off, it didn’t have the staying power of its predecessor, nor did it contain such a unifying, powerful, rugged and raw emotional core.

Regardless of whether or not I was as enamored with Jungle as I was with the debut, I continued to remain excited about Hunt’s subsequent work. For a time, it seemed that the controversial Popular, the follow-up to Jungle, was prepped for a legitimate release. Then, slowly but inexorably, rumors began circulating online that Blue Note, the label set to carry and promote Popular, was having “creative differences” with Hunt. Initial promo EP’s and full-length promo copies were sent to radio stations, and then, out of nowhere, BAM!! The plug was pulled. Popular was stillborn, and while all the tracks from the album eventually made their way to the internet, the damage was done. Hunt was understandably pissed, and seemed to beat a hasty retreat from the spotlight in lieu of what had occurred.

Which, in a rather circuitous fashion, brings us to the release of “What Were You Hoping For?” After reading the above paragraphs, I’m sure you know that I was awaiting this with baited breath. It’s hard to dig a musician so much, only to get to the point where you must at least contemplate the possibility that you may never hear anything from them again. So, in light of all of this, does Van Hunt’s long-awaited, brand-new, official, oft-discussed, third (fourth?) album live up to the hype? The answer, dear friends, is an emphatic and unequivocal YES. In fact, Hunt is bolder and more experimental here than he has ever been before, taking risks and chances that pay off in dividends throughout the record. I can’t think of anyone, in ANY musical era, who has sounded like this. This is Prince, Jimi, Beatles, Stones, Clash, Bad Brains, Pink Floyd, Badu, Maxwell, D’Angelo and a million others all rolled up into one, but, most importantly, it remains distinctly VAN HUNT. From the opening crunch of “North Hollywood” to the closing strains of “Mysterious Hustle,” this music exists purely on its own terms, and in its own stratosphere, with many exhilarating twists and turns along the way. “Watching You Go Crazy Is Driving Me Insane” is straight-up punk rock, the gnarliest and grimiest thing in Hunt’s oeuvre. “Designer Jeans” and “Plum” are practically genres unto themselves; awash in lust and psychedelia and full of alien melodic changes that only Hunt could write. “Falls (Violet)” and “Moving Targets” show that Van still exceeds at writing achy, heartbroken ballads. “Eyes Like Pearls” is the most straightforward thing here, no coincidence then that it was issued as the album’s leadoff single. It’s a stomping, almost Zeppelin-esque romp that is beyond joyous to listen to and revel in; it makes me remember everything that I’ve always dug about Hunt while still propelling his song-craft into the future. It also keeps the listener’s attention focused on the second half of the record, which is magnetically fascinating in how esoteric it is. “A Time Machine Is My New Girlfriend” continues in the punk vein of “Watching You Go Crazy…,” though its central message is more tongue-in-cheek, and less despairing. The title track and “Cross Dresser” are out-of-left-field treasures, and when “It’s A Mysterious Hustle” finally ends the whirlwind ride, one is left to ponder what it is that has just happened for the last hour. The simple solution to that quandary? Play the shit again!!!!

Aug 4, 2011

August 4, 2011.

Wow, way overdue on adding new posts here. Part of it is that I’ve been absolutely overwhelmed with great records the last few weeks…not a bad thing at all, but it left me struggling to decide on what to post and what to leave a mystery, the “secret stash” that all true collectors hold close, only revealing it to the most trusted of confidants. Two particular events contributed to the addition of 100+ records to the stacks recently. The first was accidentally stumbling upon a jackpot of rare soul and funk LP’s at a thrift store, with all the records being sold for $3 apiece. The second was the generosity of a family friend, who was kind enough to let me dig through her entire collection and take whatever I wanted for free, these records also being a treasure trove of exclusively exquisite ‘70’s funk and soul. So, fast-forward to now, where I’ve had a couple of work-free weeks to explore these gems, and I still haven’t even scratched the surface…so many amazing finds. I’ll begin with the records below, and will try not to be such a stranger to my own blog through August and September. Lots of catching up to do!

Johnny Jenkins: "Ton-Ton Macoute"

$3 at a thrift store for this very rare and sought-after platter. Anyone wondering where Beck got most of his ‘90’s ethos from need look no further than this record, perhaps most famous for containing the sample that served as a foundation for “Loser.” That is a mere footnote, however, to the magic that occurs here, with southern soul belter Jenkins being backed by none other than the Allman Brothers Band, before Duane’s tragic death. I like the Allman Brothers and everything, but damn, I never dreamed they could be this funky!! It’s like a completely different band, with the only telltale sign of their trademark style being Duane’s stinging slide guitar work. “I Walk On Gilded Splinters” is the most-referred-to cut on this LP, featuring not only the entire “Loser” sample but also an incredible introductory breakbeat, funkier than nine cans of shaving powder. The record proceeds in an even darker direction from there on out, positively reveling in its late-night, swampy, voodoo-funk vibe. At one point Jenkins tackles Muddy Waters’ classic “Rollin’ Stone,” and he sounds positively haunted by the spirit of the Delta, a harrowing yet riveting experience for the listener. This is music for incantations, spells, soul-searching…you will not be the same after the needle skids onto the dead wax.

Cymande: "Promised Heights"

When I came across this in the same thrift store stack that I found the Johnny Jenkins LP in, I was completely taken aback. I had only ever seen reissues of this available, and never thought I would find an original copy, much less one in such pristine shape. This is one of those records that stands outside of any easily-assumed labels or categories, with Cymande brewing up a concoction of influences that incorporates everything from funk and soul to reggae, dub, afro-beat, afro-cuban, soukous and calypso. While their hardest-hitting funk cut, “Brothers On The Slide,” is here in all its glory, there is much else to gravitate towards on this LP. “Pon De Jungle” opens up the album with a hypnotic chant, followed by the Mandrill-esque funk of “Equatorial Forest.” “Brothers…” finds one of the vocalists in the group doing their best Curtis Mayfield impression, yet the percussion breakdown in the middle is a clear indicator that this is no windy city soul record. “Changes,” perhaps my favorite song on the album, cultivates a sublime, mellow, meditative mood, awash in languid guitars and a drifting, lazy tempo. Other cuts that stand out are the title track and the closing “Sheshamani,” further proof that Cymande were on to something unique with their heady mix of styles. Why the band never achieved greater success in their own time will forever be a puzzlement, so thank goodness the hip-hop generation picked up on them, even if it was decades later. I will continue to maintain, however, with Cymande and all other obscure artists re-discovered by break-hungry DJ’s—look further than the samples. There is untold wealth lying beneath the facile surface of your favorite drum-break.

Herbie Hancock: "Flood"

This is probably the record that’s been on my want-list the longest. Long before I was digging deep into the back catalogues of offshoot soul labels and regional diasporas, this was still on my radar, with Herbie being one of my early gateway musicians into the ever-expanding world of jazz-funk. This double LP features the Headhunters live and in their prime, classic line-up intact, with Herbie on keys and synths, Bennie Maupin on sax, Bill Summers on percussion, Paul Jackson on bass, Mike Clarke on drums, and newer addition Blackbird McKnight on guitar. Many of the well-known tunes from the Headhunters’ studio albums of the era get a complete revamp here, like in “Actual Proof,” where Herbie plays acoustic piano instead of Fender Rhodes, or in “Chameleon,” where the synth solo from the studio version becomes completely negated in the wake of Herbie’s live take on the tune, which features not so much a synth solo as it does a synth meltdown, a barrage of futuristic fireworks from inside the mind of a computer as fused with the mad genius of a jazz musician. The band is incendiary throughout the set, though Blackbird McKnight’s contributions are more tentative than they would be on future Headhunters efforts and in his subsequent work with Funkadelic. The rhythm section of Mike Clarke and Paul Jackson is one of the most telepathic ever recorded to tape, with their interlocking lines and grooves only able to be explained by the phenomenon of extrasensory perception. For anyone that has ever fancied themselves even a casual collector and/or fan of ‘70’s jazz-funk-fusion, this album is an essential listen.

Edwin Birdsong: "Edwin Birdsong"

I love Edwin Birdsong’s music. He’s such an odd cat, yet there is something very intriguing about his offbeat, idiosyncratic solo efforts. This self-titled release on the Philly International label is more streamlined and club-oriented than his earlier funk-rock experiments for Polydor, but the funny thing is, even when Birdsong is attempting a more mainstream sound, he can’t quite swing it, so innately quirky is his own muse. “Cola-Bottle Baby” and “Phiss-Phizz” blend into each other, and while the disco pulse beneath both tracks is unmistakable, the acid guitar shredding by Ronald “Head” Drayton atop the groove has no peer in the disco world. It’s some sort of unwieldy fusion of dance-thud and psychedelic metal, and only Birdsong could make it work. Other tracks have a mellower feel to them, especially the spacy “Lollipop (Slow).” Like all of Birdsong’s albums, there really is no context in which this music belongs, which is what makes it all so wonderful.

Rodriguez: "Cold Fact"

Oh WOW!! OG pressings of this record are rare as hen’s teeth in the states, when I found this for a measly $10 at one of my favorite Portland record stores I practically tripped over myself in bringing it to the counter for purchase. I’d heard all the hype about Rodriguez when his two Sussex LP’s were reissued by Light In The Attic a few years back, but at that time I had other vinyl obsessions on my mind and was fairly oblivious to the luminous qualities of this cat’s unique brand of folk-rock. Everything here is incredible, although “Sugar Man” and “Only Good For Conversation” are certainly the standout tracks, a fact not lost on modern progressive radio stations who played these tunes to death when the reissues first came out. Rodriguez has a cynical, bitter bent to his writing that sets him apart from his wide-eyed, idealistic contemporaries in the folk-rock movement of the early ‘70’s, with Dennis Coffey’s distorted guitar and production skills proving the perfect foil for the bile lurking beneath the surface of the lyrics. It really is no surprise that this album came out of Detroit, as the specific, pointed kind of grittiness found here is stock-in-trade for the Motor City sound. This LP deserves a treasured place right next to your Stooges and Funkadelic records, more subtle perhaps than those bands but still completely comfortable in their company.

Apr 2, 2011

April 2nd, 2011.

I had very little else to say on the blog during February and March, the loss of Barry Hampton influenced and affected everything else in life. Barry and I loved records and often discussed them at length, and so to dig back into my own stacks brought sadness and melancholy memories, tears to my eyes, that inescapable VOID that cannot and will never be filled. However, it was necessary to remind myself that, while these memories would stay with me always, I also needed to move beyond them to move forward, to “walk on” as Barry himself would say. And so I have, slowly but surely, though every time I hear “She’s Always In My Hair” by Prince I still weep, as I do when I hear “The Song Is Familiar” by Funkadelic. Somehow the music continues, the cycles and circles broken and unbroken simultaneously. Here are some more funky grooves for Barry and the rest of the known and unknown universe…love from the four corners…

Olatunji: "Soul Makossa"

To me, this LP deserves a place in history right next to the Incredible Bongo Band records in terms of having an unlimited wealth of breaks and beats; Olatunji is more famous for his earlier Afro-Percussion efforts of the ‘60’s, while this album has achieved little more than cult status, at best. One listen, though, will convert even the most jaded beat-seeker, and really, the beats and breakdowns here just scratch the surface of how monumental this music truly is. Joe Henderson is the saxophonist, playing in a mode unlike anything else in his musical legacy, and famed producer and Miles Davis alum Reggie Lucas is on guitar, with the recording year (1973) being early enough in his career for him to still be billed as “Reginald.” Meanwhile, Olatunji and his army of percussionists stomp through the grooves like a herd of rampaging rhinos, trampling everything in their path as Lucas and Henderson provide psychedelic musings on the top end of things. Songs like “Takuta” and “Dominira” live outside of time and space, and when the initially muted drums of the former shift into full tonality, the band takes the expressway to the skull directly, rattling the psyche and leaving reverberations in every nook and cranny of the brain. Even the cover of Manu Dibango’s legendary “Soul Makossa” demonstrates a flavor not present in the original; though this album was surely an attempt to cash in on that song’s hit potential circa the early ‘70’s, it breaks outside of those boundaries to carve out its own path, and what a path it is.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)